by Libby Holden

Libby Holden is a Schubert Club board member and has been a member of Theoroi, the Schubert Club’s young professionals group, for the last four years. She credits her grandmother, Harriet, for encouraging her love of the performing arts and volunteering. Libby lives with her partner and their rescue dog in Minneapolis.

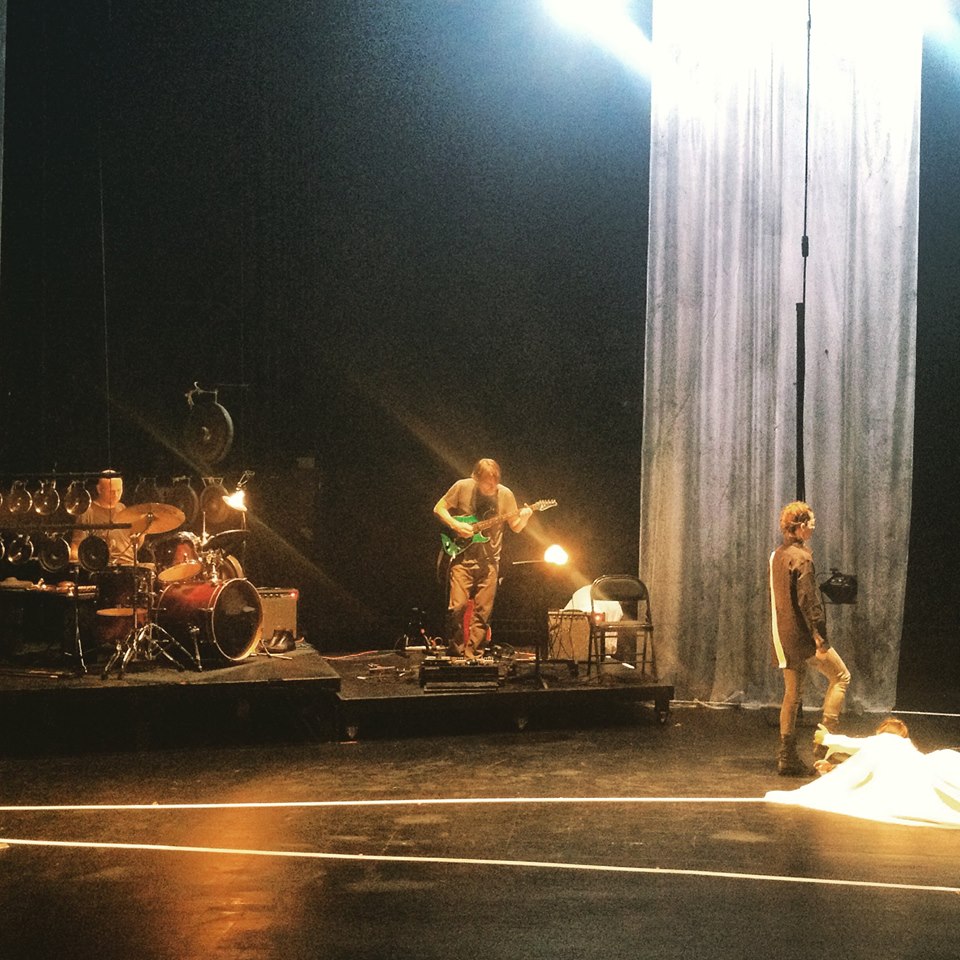

We asked Libby to interview Orpheus Unsung producer/director Mark DeChiazza in preparation for this week's world premiere performance of the work at the Guthrie Thursday through Saturday. Orpheus Unsung casts the electric guitar as the disembodied voice of Orpheus, who seeks to reverse fate and regain an irrevocably lost Eurydice. In this wordless opera, the myth is shattered and ultimately re-made within a space that fragments story and identity, and hangs in teetering balance between solidity and hallucinatory illusion. Orpheus's journey is illuminated in new musical/visual/theatrical language, as sound collides and fuses with the expression of the body, cinematic imagery, and transformations of physical space. Read last week's interview with Orpheus composer Steven Mackey here. Special thanks to Libby for putting this interview together for us.

photos by Janelle Jones

Hi Mark. Your website and other materials suggest that this has been a long, meandering road to be able to present this work with you and Steven.

It has been a long, meandering road. I can illuminate that for you.

This was the first project that Steve and I ever talked about doing when we first met. That was 2009, at the Ojai Music Festival. We were both involved in major productions there, and liked what each other were doing, respectively. So, that was when Steve and I first agreed to make a piece with electric guitar and dance. We didn’t have any sort of venue or producer and ended up making a lot of other projects together before this ever could possibly happen. That’s part of the meandering.

It has been seven years in development, though. How do you stay excited about something that takes that long, from concept to delivery?

It’s interesting. I mean obviously the piece has been something that Steve and I have talked about a lot, but we hadn’t ever talked about the fear of the piece.

The fear?

The fear of the piece. Yeah - this is a really ambitious work for each of us. It calls on both of us, in our own way, to go deeply back into something that we did before, and to bring it into conversation with the work we are doing now. Until we had our residency at Carleton College, where we did an initial showing of Orpheus Unsung, it felt very successful. People responded to it, and we felt like, “okay, we did this thing.” Then we went out for coffee and we both confessed to each other that this piece has been something that has been terrifying us for years. When something feels deeply personal and important, then the stakes are much higher. Both of us felt like this was a push into the unknown. The other projects we had done together, I wouldn’t say they were unambitious, but they didn’t feel nearly as ambitious as this.

That makes a lot of sense, so there’s this fear driving you guys, in addition to the art.

Yeah, fear and desire, together.

I think that is actually a part of the Orpheus myth.

We didn’t have the Orpheus myth to begin with. It felt like this was the Orpheus myth for each of us, in a way, because we’re both going back to works we did in our past, trying to bring them into the present, and make them relevant and new. With the hubris and the necessity of that, it’s all of those things together.

You and Steven could have taken Orpheus Unsung anywhere. Sure, it has some of its creative juice in Northfield, but you could have debuted this in really any place. Why Minneapolis?

People love this piece. They love what we’re doing with it. Talking about it, before we made it, was very difficult. You can’t show people something until you get a chance to make something, but Kate Nordstrum and Liquid Music gave us a chance to make something. She had the faith in us and what we were doing, to trust us and to let us do something. That’s huge, and that’s why Minneapolis.

There’s already a lot of other interest in it, but that outside interest wouldn’t have happened if Orpheus Unsung hadn’t gone to Minneapolis first.

What’s your next seven-year project? It sounds like projects like this don’t come up often in a director’s life.

I had a career as a dancer, before that I was a filmmaker and set designer and visual artist. I didn’t start as a dancer, but a substantial part of my career was as a dancer. Then, as I built my career as a director and I started working in music and film again, I never really went back into dance. But, I always use what I learned in dance, in filming; I use it in editing; I use it in everything.

With Orpheus Unsung, I’m going back to this thing that I really, consciously left behind and trying to bring it back into the present again, bring it back with me. And that was an incredibly fearful experience. I set it as a task for myself, on purpose, because I knew that it kind of scared me, and I thought it was appropriate for this project that I should do that. But, the discovery that I had in the process was really incredible. I think that I re-learned what is special, what is challenging, what is beautiful and what is difficult about dance. Things I once knew but forgot. This project brought that part of my history back into my practice in a more concrete way, and I think that it will probably stay there.

That’s so cool.

That’s what I think changed, and that was not what I expected when I started this.

SEE THE WORLD PREMIERE OF ORPHEUS UNSUNG LIVE AT THE GUTHRIE THEATER THURSDAY JUNE 16, FRIDAY JUNE 17 AND SATURDAY JUNE 18 AT 7:30PM

Follow Mark:

www.markdechiazza.com

Follow Shubert Club/Theoroi:

@TheoroiProject

@schubertclub

http://schubert.org/

http://schubert.org/theoroi/

https://www.facebook.com/schubertclub/

FOLLOW LIQUID MUSIC FOR UPDATES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS:

Twitter: @LiquidMusicSPCO (twitter.com/LiquidMusicSPCO)

Instagram: @LiquidMusicSeries (instagram.com/liquidmusicseries)

Facebook: www.facebook.com/SPCOLiquidMusic/